ASCO’s Media Issue Briefs provide succinct overviews and relevant data on major policy issues impacting patients with cancer and the physicians who care for them. These briefs are designed to be especially helpful for journalists, offering background information on key issues across health policy today. Access ASCO’s full collection of Media Issue Briefs.

Issue Overview

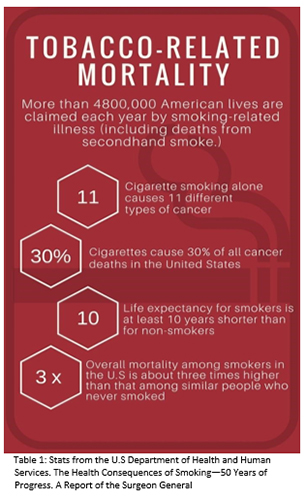

Each year, 660,000 Americans are diagnosed with a smoking-related illness and 343,000 people die from cancer related to tobacco use.1 Cigarette smoking alone causes 11 different types of cancer (acute myeloid leukemia and cancers of the lung, oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, kidney, bladder, colorectum, and uterine cervix) and causes 30% of all cancer deaths in the United States.2

Research shows that individuals with cancer who continue to use tobacco during their cancer treatment have more negative side effects, higher rates of cancer recurrence, and shorter survival than non-users. Growing evidence also suggests tobacco use by patients with cancer can complicate a wide variety of treatments, including radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery. In addition to the tremendous human toll of tobacco, our nation spends approximately $170 billion annually on tobacco-related medical care for adults alone.3

Although cigarette smoking has declined significantly since the release of the first Surgeon General’s Report, recent studies indicate that pockets of the United States and world are still disproportionally impacted by tobacco-related illness and death. ASCO supports efforts to eliminate tobacco-related disparities as part of its commitment to reducing cancer disparities, overall.

A 2016 study found that, among U.S. adults, 40 million are cigarette smokers and up to 40% of cancer deaths in men, in southern states, are caused by smoking.4

A 2017 study found smoking and its side effects cost the world's economies more than $1 trillion and contribute to the deaths of about 6 million people each year, a number expected to rise by more than one-third by 2030. The report also showed that 80 percent of the world's 1.1 billion smokers are living in low and middle-income countries.5

ASCO has advocated at both the state and federal levels for reducing tobacco-related disease and protecting public health. The Society has spearheaded many efforts to regulate and limit the sale of cigarettes and other tobacco products, and has collaborated with the nation’s leading public health and medical organizations to help pass meaningful policy changes.

State Efforts on Tobacco Use

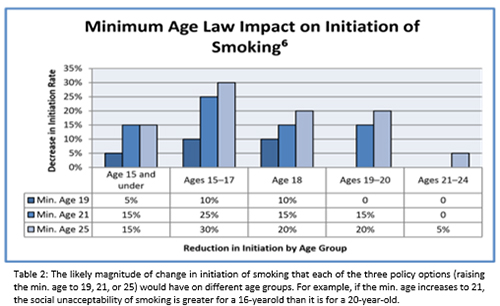

In the United States, the minimum legal age to use tobacco products is set by the federal government at 18 years of age, but state and local governments can set older ages. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report stated that raising the minimum legal age would result in reductions in tobacco use initiation and prevent hundreds of thousands of premature tobacco-caused deaths.6

The minimum legal age has been raised to 21 in three states (Hawaii, California, and Maine) and at least 170 localities in 13 states, including Boston, New York City, and Chicago.7

ASCO has outlined its support of legislation to increase the minimum age in a recent Policy Brief.

FDA Regulation of Tobacco Products

The passage of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act in 2009 legislation, strongly supported by ASCO, gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products. FDA regulation of these products has led to many improvements in tobacco control, including:

- Restricting tobacco marketing and sales to youth

- Requiring smokeless tobacco product warning labels

- Ensuring "modified risk" claims are supported by scientific evidence

- Requiring disclosure of ingredients in tobacco products

- Preserving state, local, and tribal authority

In 2017, the FDA announced a new strategy to address tobacco-related disease and death. The agency seeks to develop a plan to reduce the nicotine levels in combustible cigarettes to non-addictive levels.

E-Cigarettes and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), which include electronic cigarettes, are devices capable of delivering nicotine in an aerosolized form. ENDS use by both adults and youth has increased rapidly and may be harmful, particularly to youth, if they increase the likelihood that nonsmokers or former smokers will use combustible tobacco products or if they discourage smokers from quitting. From 2011 to 2014, current e-cigarette use among high school students rose from 1.5% to 13.4%, and among middle school students from 0.6% to 3.9%. Additionally, spending on e-cigarette advertising increased from $6.4 million in 2011 to an estimated $115 million in 2014.8

In 2015, the ASCO and American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) issued a joint policy statement that recommended additional research on these devices, federal, state, and local regulation of ENDS, manufacturer requirements to register with the FDA and report all product ingredients, and prohibitions on youth-oriented marketing and sales.

In 2016, the FDA used its congressionally-mandated authority to regulate cigars, hookah tobacco, electronic cigarettes and other ENDS. ASCO applauded this action as a crucial step in further regulating deadly tobacco products and ascertaining the true risks and potential health benefits of using ENDS.

“In the 50 years since the [U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health] release, tobacco use has declined considerably. More research on the harmful effects of smoking, as well as the dangers of secondhand smoke, have raised awareness and discouraged large numbers of Americans from using tobacco. Most importantly, it has prompted federal, state and local government to pass laws regulating cigarettes, protecting Americans from secondhand smoke exposure and establishing excise taxes and other regulations that discourage teens from starting to use tobacco.” – ASCO Chief Executive Officer Clifford A. Hudis, MD, FACP, ASCO Honors the 50th Anniversary of the First U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health (2014)

For More Information

- ASCO’s policy statement on electronic nicotine delivery systems

- ASCO’s updated policy statement on tobacco cessation and control

- ASCO’s tools and resources on tobacco cessation

- ASCO in Action offers the latest news and information on this and other cancer policy topics

- To schedule a media interview with an ASCO spokesperson or oncology expert, please contact mediateam@asco.org

- "Cancer and Tobacco Use." CDC Vital Signs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/cancerandtobacco/index.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Printed with corrections, January 2014. surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf.

- Xu, Xin, PhD, Ellen E. Bishop, MS, Sara M. Kennedy, MPH, Sean A. Simpson, MA, and Terry F. Pechacek, PhD. "Annual Healthcare Spending Attributable to Cigarette Smoking - An Update." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 48.3 (2015): 326-33. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749379714006163?via%3Dihub.

- Lortet-Tieulent J, Goding Sauer A, Siegel RL, Miller KD, Islami F, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, Jemal A. State-Level Cancer Mortality Attributable to Cigarette Smoking in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1792-1798. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6530.

- U.S. National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 21. NIH Publication No. 16-CA-8029A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products. Rep. N.p.: Institute of Medicine, n.d. Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products. Institute of Medicine, Mar. 2015. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18997/public-health-implications-of-raising-the-minimum-age-of-legal-access-to-tobacco-products.

- "States And Localities That Have Raised The Minimum Legal Sale Age For Tobacco Products To 21." Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, n.d. Web.

- Arrazola, Rene A., MPH, Tushar Singh, MD, PhD, Catherine G. Corey, MSPH, Corinne G. Husten, MD, Linda J. Neff, PhD, Benjamin J. Alpelberg, PhD, Rebecca E. Bunnell, PhD, Conrad J. Choiniere, PhD, Brian A. King, PhD, Shanna Cox, MSPH, Tim McAfee, MD, and Ralph S. Caraballo, PhD. "Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2014." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64.14 (2015): 381-85. Cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17 Apr. 2015. cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6414a3.htm?s_cid=mm6414a3_w.